Introduction

The period of the Hundred Schools of Thought, also known as the Golden Age of Chinese philosophy, was a time of extraordinary intellectual ferment in ancient China. From the 6th to the 3rd century BCE, during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, a plethora of philosophical schools and thinkers emerged, each offering their unique perspectives on ethics, politics, society, and the cosmos. This article takes you on a captivating journey through the main schools and philosophers of pre-Qin China, exploring their key concepts, historical context, and enduring influence on Chinese civilization.

Historical Background

To understand the emergence of the Hundred Schools of Thought, it’s essential to grasp the historical context of the Spring and Autumn (770-476 BCE) and Warring States (475-221 BCE) periods. This was a time of great upheaval, as the once-mighty Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was in decline, and rival states vied for power and hegemony. The breakdown of the old feudal order and the rise of a new class of scholars and officials created a fertile ground for intellectual debate and the birth of new ideas.

The term “Hundred Schools of Thought” is a figurative expression, as there were not exactly one hundred schools. However, it reflects the diversity and richness of philosophical thought during this period. The main schools that emerged were Confucianism, Daoism, Mohism, Legalism, School of Names, School of Yin-Yang, and others.

Confucianism

Confucianism, founded by Confucius (551-479 BCE), is perhaps the most influential philosophical tradition in China. Confucius emphasized the importance of moral cultivation, proper social relationships, and good governance. His core teachings include:

- Ren (仁): Benevolence, humaneness, and the highest Confucian virtue.

- Li (礼): Ritual propriety, etiquette, and the proper way of conducting oneself in society.

- Yi (义): Righteousness, justice, and moral appropriateness.

- Xiao (孝): Filial piety, respect for one’s parents and ancestors.

- Zhong (忠): Loyalty to one’s superiors and the state.

Confucius believed that by cultivating these virtues, individuals could become junzi (君子), or “gentlemen,” and contribute to a harmonious and well-ordered society. He also emphasized the importance of education and learning, as reflected in his famous saying, “In education, there should be no class distinctions.”

Confucius’ teachings were further developed by his followers, notably Mencius (372-289 BCE) and Xunzi (c. 310-235 BCE). Mencius stressed the innate goodness of human nature and the importance of moral education, while Xunzi argued that human nature is inherently bad and needs to be shaped through strict rules and rituals.

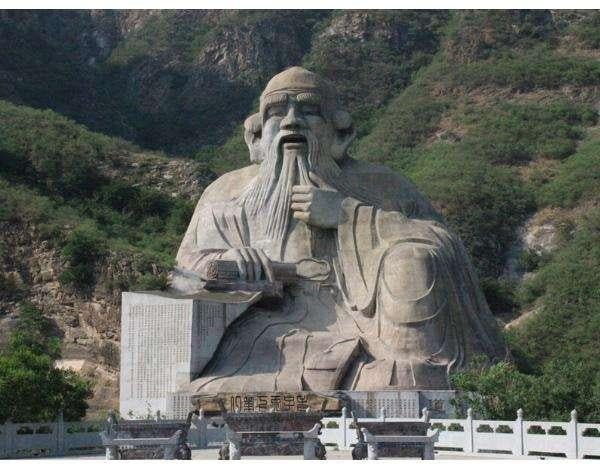

Daoism

Daoism, also known as Taoism, is a philosophical and religious tradition that emphasizes living in harmony with the Dao (道), or the “Way.” The two main texts of Daoism are the Dao De Jing, attributed to Laozi (6th century BCE), and the Zhuangzi, named after its purported author, Zhuangzi (369-286 BCE).

Key concepts in Daoism include:

- Dao (道): The ultimate reality, the source and pattern of all existence.

- De (德): The power or virtue that arises from being in harmony with the Dao.

- Wu wei (无为): Non-action, or effortless action in accordance with the Dao.

- Ziran (自然): Naturalness, spontaneity, and being true to one’s nature.

Daoism emphasizes simplicity, spontaneity, and the rejection of social conventions and rigid rules. It sees the ideal state as one of harmony between humans and nature, where individuals live in accordance with the natural flow of the Dao.

Mohism

Mohism, founded by Mozi (c. 470-391 BCE), was a philosophical school that stressed universal love, social equality, and pragmatism. Mozi’s core teachings include:

- Jian ai (兼爱): Universal love, the idea that one should care for all people equally.

- Fei gong (非攻): Condemnation of offensive warfare and promotion of defensive warfare only.

- Jie yong (节用): Frugality and the efficient use of resources.

- Tian zhi (天志): The will of Heaven, which is benevolent and desires the welfare of all people.

Mohism was known for its emphasis on logic, science, and technology. Mohists made significant contributions to fields such as optics, mechanics, and fortification. However, the school declined after the Warring States period and was largely absorbed into Confucianism and Daoism.

Legalism

Legalism was a philosophical school that emphasized strict laws, rewards, and punishments as the key to maintaining social order and strengthening the state. The main proponents of Legalism were Shang Yang (d. 338 BCE), Han Feizi (c. 280-233 BCE), and Li Si (c. 280-208 BCE).

Key concepts in Legalism include:

- Fa (法): Laws and regulations that apply equally to all people.

- Shu (术): Statecraft, the techniques and strategies used by the ruler to control the state.

- Shi (势): Power and authority, which the ruler must use to enforce the law and maintain order.

Legalists believed that human nature is inherently selfish and that people can only be controlled through strict laws and punishments. They advocated for a strong, centralized state with a powerful ruler at the top. Legalism played a significant role in the unification of China under the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) but fell out of favor in later dynasties.

School of Names

The School of Names, also known as the School of Logicians or Sophists, was a philosophical school that focused on logic, language, and the relationship between names and reality. The main figures associated with this school are Deng Xi (6th century BCE), Hui Shi (c. 380-305 BCE), and Gongsun Long (c. 325-250 BCE).

The School of Names is known for its paradoxes and logical puzzles, which were used to challenge conventional thinking and expose the limitations of language. For example, Gongsun Long’s famous “White Horse Dialogue” argues that “a white horse is not a horse,” as the concept of “white horse” is distinct from the concept of “horse.”

While the School of Names did not have a lasting influence as a distinct philosophical tradition, its ideas and methods influenced later Chinese philosophy, particularly in the development of Buddhist logic and the Neo-Daoist movement of the Wei-Jin period (220-420 CE).

School of Yin-Yang

The School of Yin-Yang, also known as the School of Naturalists, was a philosophical school that focused on the concept of yin and yang, the two complementary forces that make up the universe. The main text associated with this school is the Yijing, or Book of Changes, which dates back to the early Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE).

Key concepts in the School of Yin-Yang include:

- Yin and Yang: The two opposing but complementary forces that underlie all phenomena in the universe. Yin is associated with darkness, passivity, and femininity, while Yang is associated with light, activity, and masculinity.

- Wuxing (五行): The Five Elements or Five Phases (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) that interact with each other in cycles of generation and destruction.

- Qi (气): The vital energy or life force that animates all things in the universe.

The School of Yin-Yang emphasized the importance of understanding the natural world and living in harmony with its patterns and cycles. Its ideas influenced later Chinese philosophy, medicine, and science, particularly in the development of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the concept of feng shui.

Other Schools and Thinkers

In addition to the major schools mentioned above, there were many other philosophical traditions and thinkers during the pre-Qin period, including:

- Agriculturalism: A school that emphasized the importance of agriculture and the virtues of a simple, rural life.

- Militarism: A school that focused on military strategy and the art of warfare.

- Yangism: A hedonistic school that advocated for the pursuit of pleasure and self-gratification.

- Zisi (c. 481-402 BCE): A grandson of Confucius who played a key role in transmitting Confucian teachings.

- Meng Ke (c. 372-289 BCE): Better known as Mencius, he was a major Confucian thinker who stressed the innate goodness of human nature.

- Zhuangzi (c. 369-286 BCE): A major Daoist philosopher known for his witty and paradoxical writings.

- Han Feizi (c. 280-233 BCE): A prominent Legalist thinker who synthesized earlier Legalist ideas and influenced the Qin Dynasty.

The Influence of Pre-Qin Philosophy

The Hundred Schools of Thought had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese civilization. Confucianism became the dominant philosophical tradition in China, shaping its social, political, and ethical norms for over two millennia. The Confucian emphasis on education, meritocracy, and social harmony continues to influence Chinese society to this day.

Daoism, with its focus on harmony with nature and the cultivation of inner peace, became a major religious and philosophical tradition in China. Daoist ideas and practices, such as meditation, breath control, and alchemy, have had a significant influence on Chinese art, literature, and medicine.

Legalism, while short-lived as a distinct philosophical school, had a lasting impact on Chinese political thought. Its emphasis on strict laws, rewards, and punishments influenced the development of the Chinese legal system and the concept of the “rule of law.”

The ideas and methods of the School of Names and the School of Yin-Yang also had a lasting influence on Chinese philosophy, particularly in the development of logic, cosmology, and the natural sciences.

Conclusion

The Hundred Schools of Thought represent a remarkable period of intellectual ferment in ancient China. The diverse philosophical traditions that emerged during this time, from Confucianism and Daoism to Mohism and Legalism, have shaped Chinese civilization for over two millennia and continue to influence Chinese thought and culture to this day.

By exploring the key concepts, historical context, and enduring influence of these schools and thinkers, we gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of the richness and complexity of Chinese philosophy. The Hundred Schools of Thought not only provide insight into ancient Chinese society but also offer timeless wisdom and inspiration for those seeking to navigate the challenges and opportunities of the modern world.

References:

The Beginning of Autumn: Liqiu, a Seasonal Turning Point in the Chinese Lunar Calendar

The Tao Te Ching – Chapter 27

The Shocking Revelation: A Chinese Female Ph.D. Student’s Fight Against Sexual Harassment

Foxconn Invests $1 Billion in Zhengzhou, Boosting China’s Tech Industry

How Chinese Netizens React to Microsoft Blue Screen Incident

The Whirlwind of Wahaha: Zong Fuli’s Resignation and the Future of a Chinese Beverage Giant

How Chinese Netizens React to Microsoft Blue Screen Incident

Crusbro: Unlocking the Treasure of Enterprise Knowledge with AI-Powered Enterprise Knowledge Management

The AI Revolution in China: Unveiling the Astonishing Progress and Societal Impact

The Curious Case of the Forgotten VIP Passengers: A Comical Tale of Airport Misadventures

Amar Yousif Sparks a Football Frenzy in China

China’s 985 Project: A Glimpse into the Nation’s Top Universities

The Curious Case of the Forgotten VIP Passengers: A Comical Tale of Airport Misadventures

The Chinese Response to the Phrase “City不City” Coined by Western Tourists

Jiang Ping’s Rise Sparks Debate and Reflection in China

The Rise of a Math Prodigy: Jiang Ping’s Controversial Journey from Vocational School to Global Math Competition

the Felicity Hughes Case Sparks Online Frenzy in China

Huawei’s Future in the Automotive Industry After Selling “AITO” Brand to Seres

Five must visit tourist attractions in Hangzhou: low-key content, have you experienced it?

China’s “Singer 2024” Is Sparking a Revolution in the Music Industry

China’s Automotive Industry: Navigating the “Juàn” Phenomenon

The 102-Year-Old Yao Healer: A Beacon of Hope in China’s Remote Mountains

The Ice Cups in China: A New Summer Trend or a Fleeting Fad?

The Harsh Reality JD.com’s Mass Layoffs: Employees Speak Out

Chinese Consumers Accuse Luxury Brand LV of Discriminatory After-Sales Policies

Chinese Steamed Buns Steal the Show at French Bread Festival!

BYD’s 5th Generation DM Technology: A Chinese Perspective on the Future of the Automotive Industry

China’s Low-Altitude Economy Soars to New Heights: A Glimpse into the Future of Aviation

Chinese Netizens Amused as Celebrities Collide at Cannes

Shanghai’s Top Universities in 2024

As a Westerner, I find the Hundred Schools of Thought fascinating. It’s remarkable how such a diverse range of philosophical ideas emerged in ancient China, and how they continue to shape Chinese culture and thought to this day.

The historical context of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods is crucial to understanding the emergence of these philosophical schools. It was a time of great upheaval and change, which created a fertile ground for new ideas and debates.

The key concepts of Confucianism, such as ren (benevolence), li (ritual propriety), and xiao (filial piety), provide a framework for moral cultivation and social harmony that is still relevant today.

I’m intrigued by the Daoist emphasis on living in harmony with nature and the concept of wu wei (non-action). In our fast-paced, modern world, these ideas offer a refreshing perspective on how to live a more balanced and fulfilling life.

The Mohist idea of jian ai (universal love) is a powerful and radical concept that challenges us to extend our compassion and care beyond our immediate circle of family and friends.

It’s interesting to see how Legalism, with its emphasis on strict laws and punishments, played a role in the unification of China under the Qin Dynasty. While it may seem harsh by modern standards, it’s a reminder of the complex political realities of ancient China.

The paradoxes and logical puzzles of the School of Names are a testament to the intellectual curiosity and creativity of ancient Chinese thinkers. They challenge us to question our assumptions and think more deeply about the nature of language and reality.

The concept of yin and yang, as explored by the School of Yin-Yang, is a powerful metaphor for understanding the complementary forces that shape our world. It’s fascinating to see how this idea has influenced Chinese medicine, art, and science.

The Daoist emphasis on inner peace and harmony with nature feels particularly relevant in our age of environmental crisis and mental health challenges. Perhaps we could learn something from the ancient Daoist sages about how to live a more balanced and sustainable life.

I wonder what Mozi would think of our modern world, with its vast inequalities and conflicts. Would he still advocate for universal love and the condemnation of offensive warfare?

The Legalist idea of the ‘rule of law’ is an important concept in modern political thought, but it’s interesting to see how it was interpreted in ancient China as a means of social control and state power.

I’m fascinated by the logical paradoxes of the School of Names. They remind me of the work of Western philosophers like Zeno and Bertrand Russell, who also used logical puzzles to probe the nature of reality and language.

The Five Elements theory of the School of Yin-Yang is a unique and intriguing way of understanding the natural world. I wonder how it compares to Western scientific theories of matter and energy.

Confucius’ famous saying, ‘In education, there should be no class distinctions,’ feels remarkably progressive for its time. It’s a reminder of the transformative power of education to create a more equitable and just society.

The story of Han Feizi, the Legalist thinker who influenced the Qin Dynasty, is a tragic one. It’s a reminder of the dangers of political power and the importance of staying true to one’s principles.

I’m curious to know more about the daily lives and practices of ancient Chinese philosophers. What was it like to be a student of Confucius or a follower of Laozi?

The Hundred Schools of Thought are a reminder of the incredible intellectual richness and diversity of ancient Chinese civilization. They offer a window into a world that is both deeply foreign and strikingly familiar, and they continue to inspire and challenge us to this day.

As someone who loves a good joke, I can’t help but wonder what kind of puns and witty remarks these ancient Chinese philosophers might have come up with. Maybe Zhuangzi had a killer stand-up routine?

This really answered my problem, thank you!

Im now not positive the place you’re getting your information, however good topic. I needs to spend some time studying more or figuring out more. Thanks for fantastic information I was on the lookout for this info for my mission.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say superb blog!

Really nice style and design and fantastic subject material, hardly anything else we want : D.